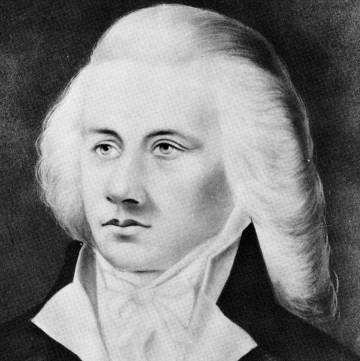

James Rumsey (1743-1792): American Genius

By Jim Surkamp

James

Rumsey was an 18th century blacksmith in Shepherdstown who transformed himself

into a modern scientist. According to ironworker/Rumsey expert, Dan Tokar,

Rumsey seemed to possess a three-dimensional laboratory in his mind's eye where

he created objects never before seen or touched by man. He would assemble these figments in his

imagination, making the resulting contraption go forward, backward, constantly

re-creating their particulars to suit his fevered fancy.

Most

of his time was spent repairing all things iron in his village, making him a

man central to much activity. He would

also be hired to study grist mills along the Town Run en route to the Potomac,

spending hours trying to figure new ways water could be directed to hit a water

wheel or other surface to generate the most motor power with the least waste of

water power. One day he obtained a copy

of John Theophilus Desaguliers' exposition on the principles of Newtonian

physics. Surely what must have freed his mind was its simple dictum: "For

every action, there is an equal and opposite reaction."

His

inspired work on directing water to create power easily segued over to a new

way of looking at this old problem: enclose water, heat it, and direct the

steamy pressure out a controlled passage.

Using only the crudest supplies, he banged out a boiler from pieces of

guns and scraps from the Antietam Iron Works directly across the river in

Maryland.

In

a scene right out of the movies he chanced to meet the revered Gen. George

Washington in September, 1784, in an inn in Berkeley Springs. When Washington

rose to leave he may have - figuratively - already agreed to not only pay for

his meal, but to pay Rumsey to build him a house in the town, and to witness a

demonstration of this intriguing man's new-fangled craft - the steamboat.

From

that day on, Gen. Washington spent inordinate amounts of his energy chasing a

dream of unifying the young country's inland natural resources and the coastal

ports, relying primarily on a canal system and steamboats like the one this

fellow Rumsey would make. Washington

started by hiring Rumsey to be the engineer to the Patowmack Company to develop

this vision.

When

Rumsey's steamboat was successfully tried on the banks of the Potomac in

Shepherdstown on December 3, 1787 with Gen. Horatio Gates, Henry Bedinger and

many others on hand, this steamboat worked some twenty years before the

better-known steamboat of Robert Fulton.

In truth, Rumsey's steamboat, which taught Fulton much, would have won a

science fair and maybe not alter history.

Venture capital was not accumulated so early in our history to

help. Crucially he yielded to the

erroneous advice of no less than Ben Franklin, who said paddlewheels would not

be needed to make the boat work just fine. He was very wrong. Fulton made sure

his boat combined paddlewheels and steam propulsion. Fulton's boat went much

faster.

Armed

with a letter of introduction from Franklin, Rumsey, the "country

mouse," set sail in 1788 for the world capital of commerce - London. During his time in Europe, he even spent a

day in March, 1789 "talking shop" with Thomas Jefferson, then our

ambassador in Paris. Each man wrote a

friend of the “interview.”

Rumsey

wrote Benjamin West March 20th. He uses a humorous code equating his designs to

a hobby horse, fearing the loss of a trade secret to other claimants to being

the steamboat’s inventor.

“I

have this day had a good ride upon my hobby.

It was by the particular request of our American Embassader that I took

this ride, and glad I was of the opertunity of mounting, having been so long

out of practice, by being in a Country where the people could not understand

the Language in which I explained hobbys gates. Mr. Jeffersons Hotel was the place appointed for me to Exercise,

and I had not been long mounted before Mr. Jefferson bore me Company, and fine

sport we should have had, would time have permitted; but dinner time came on

and Company arrived that had been invited to dine. The horse was therefore obliged to be Stabled; however Mr.

Jefferson was so pleased with hobby, that he borrowed him of me, with the

Explanation of his gates. - I know very well that what I have said will convey

to you a Very Clear idea of the business of the day, but I beg you not to

explain it to anybody (not nobody) in the Same way. To be Serious, you cannot

Conceive how attentive Mr. Jefferson has been to my business. He has been to the Hotels of a great number

of the nobility to gain their interest in my favor. But the most of them are unfortunately for me in the Country at

the Election now holding. When they

return I have no doubt but I shall succeed in the object of my Jurney.

“What

is much in my favor is Mr. Jeffersons being the most popular Embasador at the

French Court. They are Certainly fond

of america in this Country, for American principles are bursting forth in Every

quarter; it must give great pleasure to the feeling mind, to see millions of

his fellow Creatures Emerging from a state not much better than Slavery . . .’

On

March 24th, Jefferson wrote a “Mr. Willard” about his meeting or

“interview” with

Rumsey:

“(Rumsey)

His principal merit is in the improvement of the boiler, and, instead of the

complicated machinery of oars and paddles proposed by others (John Fitch - ED),

the substitution of so simple a thing as the reaction of a stream of water on

his vessel. He is building a sea-vessel

at this time in England and she will be ready for an experiment in May. He has suggested a great number of

mechanical improvements in a variety of branches; and upon the whole is the

most original and the greatest mechanical genius I have ever seen . . .”

Just

weeks after arriving in London, Rumsey landed an interview with potentially

perfect sponsors: James Watt and Mathew Boulton, the owners of the world's

largest steam engine company. They were now in the black and ready to do

business.

Boulton

had two stacks of patents and drawings to evaluate - one of Rumsey's work, the

other of a relentless rival, John Fitch - both claiming to have invented the

steamboat, both with a large state's backing and charter. Perhaps after slipping on his pince-nez and

filling his cup with tea or something stronger, Boulton's informed eye wandered

over Fitch's papers, and soon thereafter shoved the pile aside as being

spurious. He then began entering

Rumsey's world - his three-dimensional imagined laboratory - going through

Rumsey's magnificent drawings rendering, for example, the shallow draft for

steamboats that would cover the Mississippi River decades later. He perhaps was in awe of one particular

"thought experiment:"

Studying

the Archimedean screw, the corkscrew shape used to extract corks from wine

bottles, Rumsey imaginatively looked at this shape from the end,

"flattened" it to two dimensions and began calling it a

"propeller." Not bad for a man living at a time when propellers were

not yet pushing iron ships across the Atlantic and lifting airplanes through

the skies.

Boulton

brought Rumsey back in and said: "We shall make an offer to you that we

shall not make to any other," which was ownership in their company, in

exchange for Rumsey's creating for them steamboats to sell in America. Had there been email or telephones, this

could have been easy to say yes to. But

the innocent country blacksmith feared accepting the offer would somehow betray

his sponsors, including Franklin, at the Philosophical Society in Philadelphia,

who paid for his voyage. Most certainly they sent him to London to get just

such an offer as the one made.

While

Boulton fumed and waited, John Vaughn, a poor choice of advisor and agent,

continuously fed Rumsey with doubts about this sterling offer. Poor Rumsey did not know Vaughn had his own

secret designs to start a rival company in Ireland. Rumsey escaped the discomforts of this dilemma by immersing

himself happily in the building of another boat, the "Columbia Maid,"

to be tried on the Thames. He fell

deeper and deeper in debt in a city of huge debtors' prisons that were quite

full.

Finally,

the letter from Boulton came - "Sir (Mr. Rumsey) it seems you

counter-balance substance with shadows . . . You, sir, have mistaken the road

for the goal." Boulton was suggesting that Rumsey, like many inventors,

wrongly believed that creating the final drawing was the hardest part of

creating a manufactured, saleable product.

Desperate

and sponsor-less, with Vaughn's talk only that, Rumsey wrote a friend in

Shepherdstown that he was actually visiting the debtor's prisons and seeing

their wretched inmates, certain that "someday this too will be my

home." He could not tell his wife,

with two children, in Shepherdstown in a cabin on Duke Street (the site of

today's Catholic rectory).

On

the eve of the trial of the new boat, and very much in debt, Rumsey rose to

speak before the Philosophical Society in London. He was almost breaking with

stress. The room for him began to spin

and spin, then went black. When they

revived him briefly the next morning, James Rumsey's last words were: "I

must die."

Even

though he had been in London only for months, he was buried in St. Margaret's

Chapel at Westminster Abbey. They knew

already what sort of man he was.

And

there was another man also in London with common friends of Rumseys, named

Robert Fulton. A recent edition of the

"World Book Encyclopedia" notes that Rumsey died in 1792. Fulton's entry says the year he began

working "in earnest" on the steamboat was - 1792. Perhaps he got started by taking a carriage

to the London Patent Office and asking for the file marked "Rumsey."

He too knew what sort of man he was.